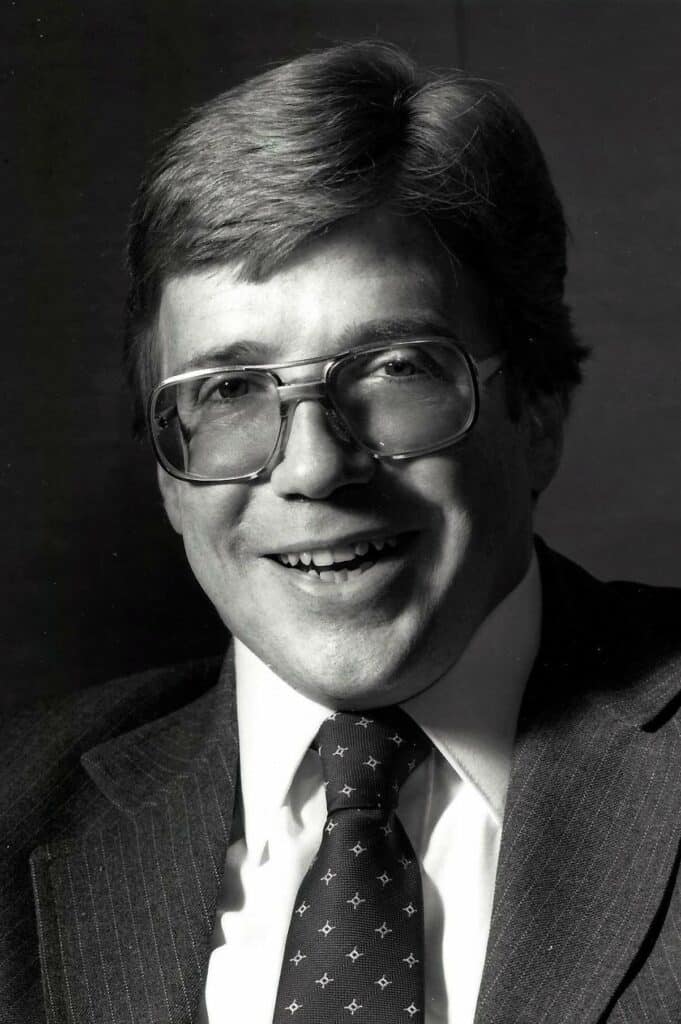

Meet Brian McLane

Jump to: My Career | School Days | Then and Now

I am an Irishman in so many ways, I’m almost a poster child for that ethnic distinction. I’m stubborn. I've been known to talk a bit, and I’m occasionally given to telling a tall tale or two, especially when the good Lord grants me an audience. I eat only as a matter of necessity, yet I absolutely love sharing huge, hours-longs meals with those closest to me. And, like so many with roots that trace back the old sod and that verdant little island home of St. Patrick and the potato famine, I’m fueled by three things above all else in life: faith, family, and friends.

That said, I’m also very atypical. I’m someone who’s spent every day of his seventy-plus years grappling with a crippling disease; in my case, what may or may not be cerebral palsy. As such, I spent my entire childhood and teenage years on crutches, then the subsequent six decades in any number of different wheelchairs. Through it all, however, I've been a regular inhabitant of one rather dubious place; the surgeon’s table. I've undergone over fourteen major operations in an attempt to do any number of things over the years; spur my body’s growth, arrest the ongoing degeneration of my outer extremities and spine, ward off further neurological damage, and, lately, ease what has become constant and often excruciating pain.

But here’s the catch. As a child, I was never raised as disabled. To the contrary. My father (a remarkable man who, as an orphan, came to America to build for himself a new life in a little Finger Lakes town called Auburn) treated me – the fifth of his six kids – just like all his children. In fact, though it was clear from early on that I was physically a little different than everyone else at school, at home, everything expected of my brothers and sister – chores, homework, yard work, family outings, school every day, and church on Sundays – was also expected of me.

In fact, it wasn’t until my family moved to Syracuse and the only place that would have me was a special-but-odd little school for the mentally and physically disabled – a loving little land of misfit toys near the Syracuse University campus called Percy Hughes – that my disability finally moved front and center in my mind.

School Days

For many, school is the single most important and formative experience they'll ever know. But I promise you, that was even more so in my case. Because, to this day, the seeds for so much of who and what I am, were planted at various points along my educational journey.

At Holy Family, for example, a tiny Catholic grammar school in Auburn, I learned the value of family, as every time I had to use the bathroom, and for as long as I was a student there, the nuns would pull one of my brothers out of class, just so he could help me answer nature’s call.

At Percy Hughes – a stigmatized educational facility, right down to its classic short bus – I first learned I had in me so many things that would later shape and define my career; leadership, listening, empathy, activism, and team-and-consensus building.

At both Westhill High and Syracuse University I learned that, on certain occasions, those in power must be compelled to rethink their antiquated ideas, if not change the way they do things, by using the only resource left to those of us often on the outside looking in; the power of the courts.

At Westhill, where my mother and father were determined to send me so that I might get a more mainstream education, my father was forced to sue the Westhill school board just so I could gain admission to their shiny new "public" high school. Yet, even then, and even after winning in court, the principal made me openly promise to my schoolmates at an assembly one day that I would never become a “distraction” to them.

Then, at Syracuse University, I had to threaten to take the university to court just to gain access to so many of the buildings at the heart of campus life, if not the undergraduate experience. As it was, I still ended up relying on a vast network of friends and classmates to lift me and my wheelchair up and down staircases, over curbs, and, at times, through giant snow drifts.

Later, as I headed off to Ohio in my very first car, where in the little town of Athens I’d earn a master’s degree in sports administration, I was able to be entirely independent for the first and only time in my life, a feeling that would, from that day forward (but especially during my days as a strong-willed colt), serve as something of a personal and professional north star foe me.

Throughout my time as a schoolboy, however, one aspect of student life won my heart like no other. I fell head over heels for the game of basketball. Junior high. High school. College. It didn’t matter. You name the level, I was obsessed with it – particularly as I sat courtside and watched my classmates whip the ball around, shoot, dribble and play defense. And though I watched from the vantage point of my wheelchair, the entire time I wished like hell I could be out there with them.

But that’s another story for another time.

(And speaking of which, if you ever wanted to see a history of the modern wheelchair, check out my photo collection; you’ll see me in everything from hand-powered chairs with bamboo caning and hard rubber wheels to a few state-of-the-art self-powered jobs, complete with deep cell batteries, fingertip controls, form-fitted seats, and – more than anything – hydraulics.)

Professional Career

I did more than my share of work in and with the private sector, especially while working with the Syracuse Chamber of Commerce after grad school, a time during which I found myself constantly trying to build bridges and foster a business climate that was robust, productive and forward-thinking -- while at the same time socially responsible.

Yet, truth be told, it wasn’t until I began working in the public sector (and as a public servant) that I found my calling and why, I believe, God put me here.

First, I began working with the Parks and Recreation Department in the Town of Cicero. There, I found myself with an ability to influence not just local ordinances, but the design and development of a handful of new green spaces and public facilities – all of them (in part, I’d like to think, because of my perspective) sensitive to the needs of the local disabled community. It didn’t seem like much at the time, but this was well before the passage of the American with Disabilities Act, so it was, in many ways, a groundbreaking moment in New York State civil rights. The way I figured it, I’d once been excluded from so many youthful activities, and if I ever had the chance to truly make a difference, I’d be damned if any young boy or girl coming behind me was going to be deprived (like I was) of so many of the moments that can make being a young person so special.

But what was really important about my time with in Cicero was that it set me on a path of public service, something that ultimately led me to the world of politics.

After Cicero, I took a job in the office of State Assemblyman Mel Zimmer, as chief of staff. Mel was not only a remarkable man and a skilled politician, but my very first mentor. The assemblyman was a natural born leader and an almost savant-like bridge-builder. What's more, I watched him marry two human characteristics on either end of the personality spectrum – empathy and steely expedience – like few men I would ever meet.

What I really loved about politics, however, is that, like basketball, it satisfied my deep-rooted desire to compete and my passion for winning. Just like basketball, in politics your candidate either won or lost, or your bill got passed or didn’t. Those things scratched an almost primal inside me.

Prior to joining Mel's team, in fact, I'd once thrown my own hat into the political ring, running for County Clerk in the early 1980's; a lifelong Kennedy Democrat trying to run down votes in the heart of what had always been (and is still) a bastion of Republicanism in the heart of New York State. And though I ultimately lost that election, the experience taught me something critical; that I’m not nearly as good a front man as I am a behind-the-scenes guy. It helped me realize what I was and what I loved most. I was, by nature, an architect, an organizer and a horse trader.

I discovered, in other words, that I’d rather make the sausage than sell or even eat it.

That realization next led me to Albany where, in the mid-1980s, I took a job in the state parks department and worked side by side with the likes of Governors Hugh Carey and Mario Cuomo. Cuomo, in particular, took a special interest in the rights of the disabled and constantly used me as a sounding board, if not his eyes and ears as he pursued a more enlightened set of laws governing such things has handicapped access and public services for the physically challenged.

Then and Now

Over the course of seven remarkable decades, it’s often felt like I’ve lived a hundred lives. I’ve sat on so many boards and committees over the years that it would make my head spin if I thought about it, including serving as a delegate to the White House Conference on the Handicapped during the first year of the Jimmy Carter administration and chairing the New York State delegation – the first person to ever do so who actually was, you know, handicapped.

As an undergraduate at Syracuse I served as color commentator for all S.U. basketball games on the school’s prestigious student station, WAER.

For a half-dozen years in the early 1970s, I served as the coach, head scout, general manager, chief cook, and bottle washer of the 7-Up Pros, one of the most storied and successful semi-pro basketball teams in Syracuse history.

I had the male athlete’s lounge in Syracuse University named in my honor.

Through a dear friend, Larry Bashe, an endowment was established in my name at the school’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Service.

And there is now a Syracuse University scholarship available for worthy disabled students, one that bears my name as the first full time, wheelchair-bound student in the history of the school.

What’s more, I have been humbled for having received any number of honors and distinctions, including the University’s ARENTS Award, S.U.'s most prestigious alumni award, as well as admission to the National Hall of Fame for Persons with Disabilities in Columbus, Ohio, where I now sit alongside giants like Franklin Roosevelt and Helen Keller.