Thoughts on a War Hero

By Brian McLane

(The following is a touch long, and for that reason I offer this, a gentle note of caution. But should you venture forward, I truly hope you’ll find the story worth the trip.)

It was the most important game of our lives, but for different reasons.

Me, as an alum and former statistician for the team, I was just about the biggest S.U. basketball fan in the world – if not the biggest. He, on the other hand, was not a Syracuse fan by design, but had grown to be one for reasons far more compelling than my own.

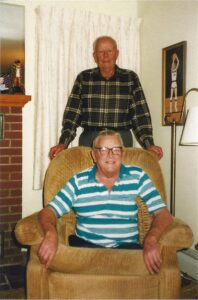

His name was Harold Lee. He hailed from nearby Kirkwood on the Southern Tier, just outside of Binghamton. And back home he was known as one hell of a mechanic and a guy who could fashion some killer picnic tables in his home workshop. His buddies at the VFW called him “Snook” (or, if they really knew him, “Snookie”). And the reason old Snook had become such a big S.U. fan was because his two oldest boys both played in Manley Field House for the good old Orange.

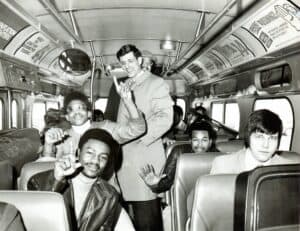

His oldest, Mike, had been an undersized forward who for three years played much taller and brawnier than his 6’3” frame. A hard-nosed kid and surprisingly effective scorer who consistently went up against opponents to whom he regularly spotted four, five, six and sometimes even seven inches, he led the Orange to the NIT once, before he and his mates finally succumbed to a deep and talented Michigan club.

His oldest, Mike, had been an undersized forward who for three years played much taller and brawnier than his 6’3” frame. A hard-nosed kid and surprisingly effective scorer who consistently went up against opponents to whom he regularly spotted four, five, six and sometimes even seven inches, he led the Orange to the NIT once, before he and his mates finally succumbed to a deep and talented Michigan club.

But the reason Snook and yours truly found each other somewhat joined at the hip in late March of 1975 – or part of the reason, anyway – was because Snook’s second oldest, Jim (or back then, Jimmy), had somehow gotten hotter than any college shooter in the country, and did so at a most opportune time for his coach and teammates. As a result, a good-but-not-great collection of gamers, hustlers and scrappers under genial Roy Danforth had just spent two weeks shocking the basketball world and now, incredibly, found themselves in their school’s very first Final Four.

The bigger reason, however, that Mr. Lee and I found ourselves unlikely partners that day was because we were both of in wheelchairs. I’d been in one for most of my life, so to me it wasn’t a big deal.

Snook, however, had been a strong and able-bodied young man for most of his first twenty years on this planet; until, that is, in an incident of “friendly fire” in the final days of World War II (and on a particularly foggy night), the nose of a Navy warship tore through the hull of his Coast Guard cutter as he slept, severing one of his legs entirely. The other might have been ripped off clean too, but for a few gallant strands of flesh, bone and ligament that did their ever-loving best to try to keep the thing attached.

Snook, however, had been a strong and able-bodied young man for most of his first twenty years on this planet; until, that is, in an incident of “friendly fire” in the final days of World War II (and on a particularly foggy night), the nose of a Navy warship tore through the hull of his Coast Guard cutter as he slept, severing one of his legs entirely. The other might have been ripped off clean too, but for a few gallant strands of flesh, bone and ligament that did their ever-loving best to try to keep the thing attached.

Three years later, however, Harold Lee would emerge from a hospital in Philadelphia a double, above-the-knee amputee, and a guy now walking with a cane and on two very crude, very rudimentary artificial legs.

Yet, just like my father taught me, Snook refused to even consider the possibility he might, somehow, be disabled. He never asked for special treatment. He simply went about his business of being a husband, father, and member of the community to the best of his ability. When he went to his boys’ games, he walked on his own and sat in the bleachers, just like everyone else. When he’d take his boys to Yankee Stadium every Summer to see those damn Yanks play (he was, understand, a Red Sox fan), he never asked for special seating. He’d just show his tickets to the usher and then slowly work his way down the concrete steps, one by one, to his family’s seats – all of which were too small to accommodate him comfortably.

You see, back then Harold Lee was an absolute brick of a man. He was a house, as solid, as strong, and as square as just about any man in the Triple Cities. In fact, at just over 6’ tall, the guy tipped the scales at roughly 240 pounds – with artificial legs.

You see, back then Harold Lee was an absolute brick of a man. He was a house, as solid, as strong, and as square as just about any man in the Triple Cities. In fact, at just over 6’ tall, the guy tipped the scales at roughly 240 pounds – with artificial legs.

But, like I said, Harold never complained. He was, after all, a proud and resolute member of Tom Brokaw’s Greatest Generation, a collection of young men and women from all walks of life, and from coast to coast, who, in defense of freedom, democracy, and the sanctity of human life the world over, sacrificed for their fellow man like no generation of Americans ever, and did so selflessly and silently, never asking for a thing in return.

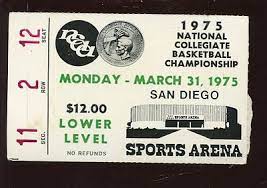

But back to our respective “biggest game ever,” one held that March in sunny San Diego, the home of that year’s Final Four.

It was 1975, remember. And in ‘75 there was simply no such thing as wheelchair accessible, nor were there any such things as access ramps. The world was just one big maze of dead ends and architectural barriers for guys like Snookie and me.

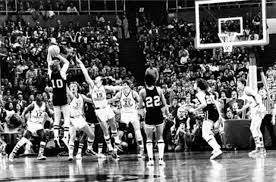

S.U.’s semi-final game against Kentucky, one played on a Saturday afternoon, was one for which we showed up early. We were so excited and so tingling with anticipation that, for a while, everything seemed almost surreal. But once we got to the arena, lo and behold, a very harsh form of reality quickly set in. Not only were there steps leading up to the arena, but the doors leading inside barely accommodated our wheelchairs. As a result, we had to spend an inordinate amount of time just trying to get in the place.

Once inside, however, things only managed to get worse. Our tickets were for seats near the floor – in fact because Jimmy was starting for Syracuse, Mr. Lee’s seat was literally on the floor. But there was no wheelchair access to there from the first level concourse. We were told by an usher that the only way to get us and our chairs down to our seats was for four ushers to physically carry us there – and that was simply not going to happen.

Once inside, however, things only managed to get worse. Our tickets were for seats near the floor – in fact because Jimmy was starting for Syracuse, Mr. Lee’s seat was literally on the floor. But there was no wheelchair access to there from the first level concourse. We were told by an usher that the only way to get us and our chairs down to our seats was for four ushers to physically carry us there – and that was simply not going to happen.

But that was only going to get us halfway home anyway, we realized. Because there’d been no accommodation made by management for courtside seating for wheelchairs. We were told neither of us would be allowed to sit in the seats for which we held tickets.

“That’s silly,” I said. “See my ticket? It’s in the sixth row just to the left of the Syracuse bench, and my friend’s ticket is literally the very first row behind it.”

“I’m sorry sir,” I was told. “We simply cannot allow you down there.”

Part of me wanted to explode. But unlike so many times in the past (and, frankly, the future) I managed to catch myself. It was then that I happened to remember reading a story in that morning’s paper that quoted the general manager of the San Diego Sports Arena. I asked to speak to him by name and did so as patiently and as calmly as I knew how.

Part of me wanted to explode. But unlike so many times in the past (and, frankly, the future) I managed to catch myself. It was then that I happened to remember reading a story in that morning’s paper that quoted the general manager of the San Diego Sports Arena. I asked to speak to him by name and did so as patiently and as calmly as I knew how.

When the guy showed up some ten to fifteen minutes later, I tried to appeal to some combination of his humanity and common sense, and told him that we had seats down low, and that we’d been assured we’d be able to sit in them.

Unfortunately, if you looked up the term “deaf ears,” you might just find the guy's photo next to it. He looked at me, all smarmy like, and explained to me almost as though I was mentally incapable of understanding that the arena had a special section for fans like us – fans in wheelchairs – and that he’d be happy to have his ushers lead us to it.

That’s when I lost it. I began threatening the guy with going public and telling the media (many of whom were assembled a short distance below us) about how two Syracuse fans in wheelchairs – one of them the father of one of the team's star players – were being treated, and that I was going to use his name each and every chance I got.

But Snookie would have none of it. “Come on, Brian,” he said calmly, smiling to the clueless and utterly tone-deaf young man staring down on him. “Let’s just go to the seats they’ve set aside for us.”

But Snookie would have none of it. “Come on, Brian,” he said calmly, smiling to the clueless and utterly tone-deaf young man staring down on him. “Let’s just go to the seats they’ve set aside for us.”

But I wouldn’t let it go and I continued to argue for the better part of the next thirty minutes or so. Finally, when I realized I was just throwing good money at bad, and that the game was now deep into its first half, I acquiesced.

And, just like the guy promised, two ushers then wheeled us up to the arena's “wheelchair seating,” which as it turned out was code-speak for section of the upper deck so far removed from the court that, I promise you, I had trouble even reading the numbers on the players’ backs, much less seeing or hearing any of the action.

I looked at the game clock. By the time we’d been ushered to our seats there were now only five and a half minutes left in the half. It was then that it hit me. It was then that I turned to my game companion and said simply, “I’m sorry, Mr. Lee. I just think that was so wrong and wrong on so many levels. I guess I just got carried away.”

He just looked at me, smiled an understanding smile, and said, “That’s OK, Brian. That’s just the way the world is.”

He just looked at me, smiled an understanding smile, and said, “That’s OK, Brian. That’s just the way the world is.”

Years later, I’d tell Jim Lee that story. I’d tell him how frustrated I’d been that day, how calm his old man had been, and how badly I felt for robbing him of roughly fifteen minutes of the most important game he'd ever have the joy to watch his son play.

Jim then confided something about that day as well. He told me something I’d not known before. He told me that that season, while walking into a high school basketball game back in Binghamton, his father had slipped on some snow still clinging to the bottom his shoe, fallen, and shattered his hip – a part of his body that had been essential to him in that it made walking on two artificial limbs even possible.

That was roughly the time, Jim said, when he began playing horribly for a run of games – horribly as his dad sat in the hospital, and horribly as his doctors broke the news to him that he'd never walk again.

So – again, unbeknownst to me – when Snook Lee flew to San Diego that very same trip to see his son play (the first time, by the way, he’d ever been on an airplane) he did so just a few weeks removed from being told by his doctor he'd have to spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

I felt sick to my stomach when I heard that. I had no idea. And I immediately began to reflect on that day and question just how over-the-top I’d been and how regrettably I’d behaved.

Jim, though, comforted me. He also confided that, even though it wasn’t anything conscious on his part, it was immediately after his dad first broke his hip that he, himself, ended up playing those three or four horrible games in a row.

Jim, though, comforted me. He also confided that, even though it wasn’t anything conscious on his part, it was immediately after his dad first broke his hip that he, himself, ended up playing those three or four horrible games in a row.

But – again, even though it was nothing conscious on his part – immediately after that, and after he’d talked with his dad a few times on the phone from his hospital room, he went on an absolute tear – a shooting streak that he has trouble explaining, even to this day. “I don’t know what got into me,” he said. “But for a few weeks there I began shooting better than just about anyone in the country – maybe even everyone in the country. I played better than I’d ever played before and better, to be honest, than I’d ever play again.”

Jim then added that he’d like to think that somewhere deep inside, especially now that he looks back, he was able to rise up for his teammates and coach because of his father, because that’s how he’d lived every day of his life, because that was the kind of determination he showed his sons and daughter all the time back home, and because that’s exactly what he would have done had he been in Jim’s shoes.

In fact, he concluded, “I have no doubt that both Mike and I ultimately became the players we did at S.U., and did the things we did, because of my dad and what he taught us.”

Which leads me to a particular song I’d like to share with you today, one that reminds me of that magical Final Four a lifetime ago. It’s a song that hit the charts around March of 1975, when I was in San Diego to watch my beloved Orange. It's also a song that reminds me of that whole experience – the good and the bad – in part because I heard it in the car coming home from the game, and in part because of something Mr. Lee had said to me just a few hours prior.

After the ushers had left us in the third deck that day, he looked at me and told me I needed to learn to just accept certain things in life because, as he said, “that’s just the way the world is.” But, you see, as much as I grew to admire old Snook, and as much as I remain in his debt for all he gave to my country, my generation, and, indeed, my school, I had to beg to differ.

Because while he gave his legs to protect the world he loved, and so many his age gave even more for that very same reason, I was a different person from an entirely different generation. We were a generation that, rather than accepting the way things were in America, occupied ourselves with how things might improve and what we could do to change them.

So, I share this song – one listed by Rolling Stone as one of the 500 Greatest Rock Songs of All Time – not only in memory of a truly remarkable man, war hero, and father of two of the greatest Orangemen I ever saw play, but in tribute to the generation that came after his; mine, a generation that never stopped asking questions, that always envisioned a better, more peaceful, more just and more accessible world, and that, much like yours truly, never met an injustice it didn’t feel it couldn’t right.

So, I share this song – one listed by Rolling Stone as one of the 500 Greatest Rock Songs of All Time – not only in memory of a truly remarkable man, war hero, and father of two of the greatest Orangemen I ever saw play, but in tribute to the generation that came after his; mine, a generation that never stopped asking questions, that always envisioned a better, more peaceful, more just and more accessible world, and that, much like yours truly, never met an injustice it didn’t feel it couldn’t right.

Thank you for sharing my thoughts with me, my friends. And thank you, Jim, for your help in piecing together this very personal reflection of a very special time for both of us.

God bless and be well,

Brian