The Convalescent Home

By Brian McLane

I would be lying to you if I said I remember everything about that day. Heck, I was barely five.

But I do remember a few things. I remember, for example, it was Spring.

I remember too, at least I think I do, that it was a Saturday. The year was – and, again, I’m pretty sure of this – 1951.

I remember, as well, driving with my mother and father to what they kept referring to as a convalescent home on South Street. Frankly, I heard them use that phrase in my mind’s ear a few times that morning, but its significance hardly caused a ripple in my young consciousness.

Apparently, putting up with a disabled son for so long – a small boy who, physically, had trouble doing so many things, some of them as basic as sitting up by himself – had taken its toll on my mother, psychically and emotionally.

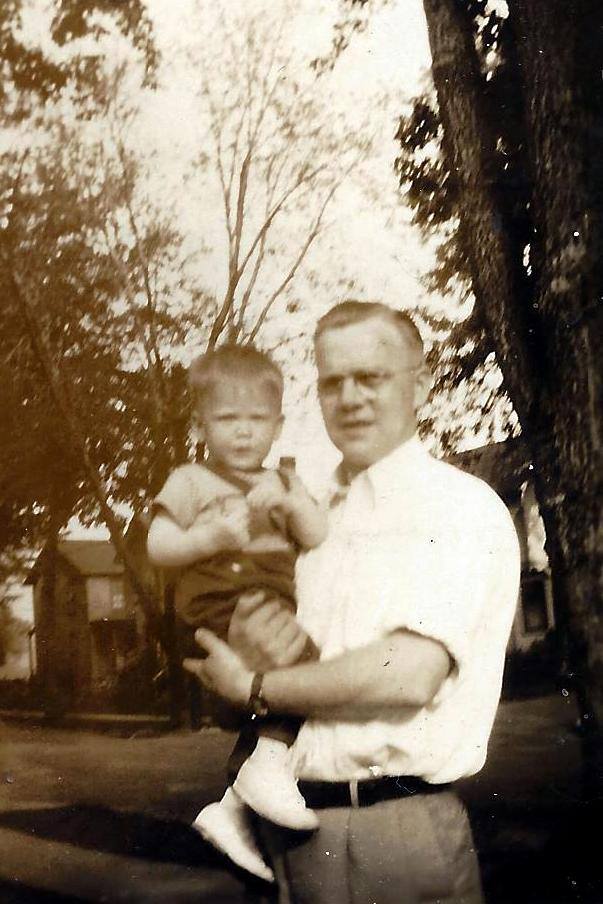

My dad – a tough-as-nails Irishman right off the boat from Dublin – was, without question, the stronger of the two. But in fairness, he worked all day and only had to confront the grim reality that something had gone terribly wrong with his son’s body two days a week; Saturday and Sunday. For my mom, on the other hand, it was a seven-day-a-week, round-the-clock responsibility from which she never received even a moment’s respite.

That afternoon, after my dad parked the car, he lifted me from the back seat, and carried me up the front steps. There we were greeted by a short, blocky woman in white with a big smile and an even bigger clipboard. The woman then invited my parents and me inside and gave us a tour of the facility.

It was OK. A little creepy and antiseptic for my tastes – and, of course, there were bars on a few the beds containing kids who just seemed to lay there and not move or react. But, like I said, it was OK.

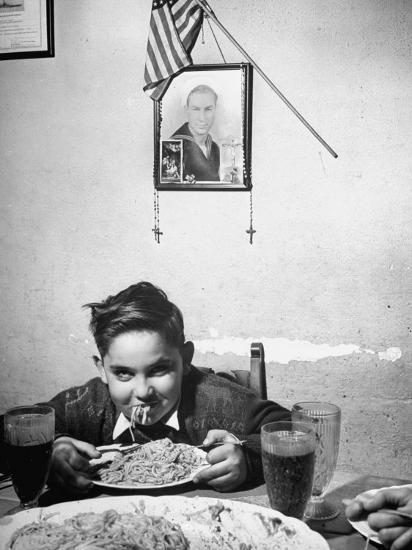

I never thought much about the place, in fact, until we were invited to sit down and eat lunch on the porch that covered much of the front of the converted brick house. Lunch turned out to be a big pile of spaghetti with fresh Italian bread on the side, along with a big glass of cold milk to wash it all down. I’d never tasted anything so good and, frankly, it was fun eating outdoors – something my large Irish family just never did.

But the reason I’m writing this now is not because my mom, dad and I ate pasta al fresco seven decades ago. I’m writing it because soon after our meal my parents rose, called to the lady and thanked her. Then, they reached down, hugged and kissed me, and promised me they’d be back to visit all the time.

I didn’t understand. I’m sure at some point they had told me they were going to leave me at the Convalescent Home, but for the life of me I couldn’t remember it.

Tears filled my eyes as my mother and father turned to leave, while a big knot formed in the pit of my stomach. The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said, “I don't think there's any point in being Irish if you don't know that the world is going to break your heart eventually.”

I just never realized my eventually would come so soon.

I began crying and, unable to get up or to chase after my parents, I just sat there and bawled as they pulled out and drove away without me.

But amid all the pain, and despite that first almost unforgivably endless night when I'd intermittently cry myself to sleep and then open my eyes with a start, feeling hopelessly abandoned, something out of a Norman Rockwell painting happened the very next day. That following morning, right after Sunday mass, two cars worth of family pulled up in front of the home and piled out. Coming to visit me were two generations of McLanes and three generations of my mother’s sprawling Irish family, the Cuddys.

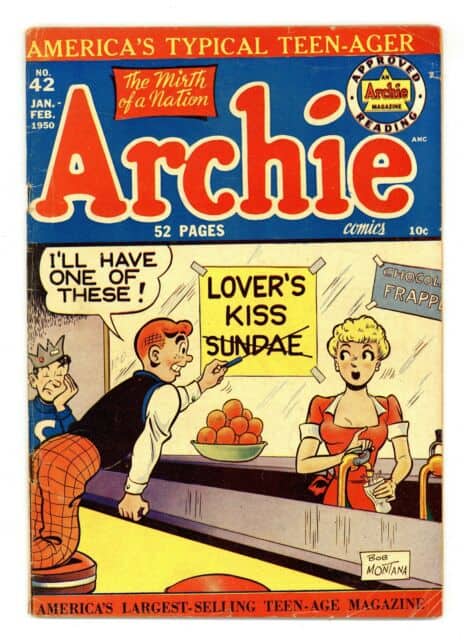

They brought me chocolate milk. They brought me donuts. They brought me comic books. They even brought me a weekly bulletin from Holy Family, our family church. But, mostly, they brought me joy. I looked around and I couldn’t believe how happy I felt to see them all, and how joyful their being there made me feel. Instead of abandoned, I felt special – and, possibly, more loved than I’d ever felt before.

And it wasn’t one day. To the contrary, every single day I was in the Convalescent Home that Summer I had family visitors. Plenty of them, in fact. Somedays it was only a handful of cousins checking in on me and looking to take over my summer home’s well-stocked TV and game room. But other times, like on weekends, it was a full complement of relatives and family members, all of them in various stages of engagement, but every last one of them as precious to me as the next. In fact, every time the McLanes and Cuddys were there, I’m not sure I ever really stopped smiling entirely.

Yet, despite that, something else fundamental happened to me that year as well. I got my first taste of independence and realized for the first time in my life that being alone was not the worst thing that could happen to a kid. In fact, I almost grew comfortable with it . And it didn’t scare me anymore – or or at least not as much asI thought it might.

I'd spend, maybe three or four months in Auburn’s Convalescent Home that Summer. My parents and extended family would, indeed, visit me like clockwork every day, and do so for hours on end – while the Cuddys, in particular, would often take over the joint, including the kitchen. And I’d make more than my share of friends, as well – especially my physical therapist, a remarkable guy named John Gavras. But looking back, I suppose that was the point at which my world view first began to take shape, if only by a tiny degrees.

Because that summer, even as a boy, I'd learned to take my first wobbly steps toward self-sufficiency – and do so in a way that, frankly, many of my able-bodied friends, even now, have not been able to master. I’d continue to always trust people as well, and to always give them the benefit of the doubt. But I'd likewise learn that no well is so deep that it’s bottomless.

What’s more, I’d learn that trust is a commodity that, once broken, is not easily mended. And I'd learn that, when cornered, I can (and will) fight with a tenacity that few people I know possess.

Now, did I learned all those things at the Convalescent Home a full lifetime ago in little Auburn, New York – much less when I was just five years old? I seriously doubt it. In fact, I’m sure I didn’t.

But, then again, were the seeds for such things first planted in me that Summer? Now that, I have to admit, is entirely possible.

Either way, regardless, and at a minimum, I remain to this day dead certain of two things that my experience in Auburn's Convalescent Home cemented in my soul.

First, few things in this world can match the healing and almost transcendent power of family. That became clear to me that very first Sunday when all those McLanes and Cuddys came barging through the door, smiles on their faces, and donuts and comic books in their hands.

And secondly, and in a far more practical way, I also came to the understanding that I'd hate the sight of pasta for the rest of my life. Because ever since that sunny, unseasonably warm, and deeply unsettling day in the Spring of 1951, yours truly has never, even once, let a single strand of spaghetti pass his lips. ###

What an amazing story and so well told. I hope I was one of those visiting relatives. One of my early recollections of the McLane family was a snowstorm in which most of us lost power and all of the McLanes came to our house on Fulton Street and gathered in the kitchen in the warmth of the kitchen stove. Gramp was there. It was in the late 1940’s.

Your insights into how you became so strong at an early age are amazing. You were really a fighter from your earliest age. Whatever it was, I am proud to call you my cousin and my friend.

Hi Brian -

Thank you for providing this inspirational tale of your early childhood.

A lot was going on during that time when The Gormley family lived across Steel Street from you. I remember a small portion of what your situation was like then. I also remember being aware of the "Childrens Home" on South St. but I don't recall what its purpose was other than taking care of children. Did that facility have a religious affiliation ?

I enjoyed talking with you at the luncheon following Mike Cuddy's funeral. I was very impressed with how you've handled your life in the face of your physical situation.

At my age - 87 in June, I'm unable to handle things as well, one of which is my e-mail in-box. So I would ask you to not put me on your roster of "Friends & Family", as I call it, for continuous messages.

Michael Cuddy Jr. is one of the people whom I have kept on that roster for keeping up with Auburn things and for enjoyment of his intellect and sense of humor.

Congratulations to you; keep up your good work.

Joe