The Birth of an “Accidental Warrior”

By Brian McLane

By Brian McLane

You may have noticed I refer to myself on my blog's home page as an “accidental warrior.” The reason I chose that particular phrase is because (and, I suppose, all evidence to the contrary) I never actually wanted to be a disabled rights advocate, or to spend my adult life trying to open up people’s eyes to the day-in and day-out plight of those of us forced to live our lives in a wheelchair.

Just the opposite, in fact.

Growing up, I just wanted to be a normal kid, like everyone else. And that’s not only what I wanted. It’s what my mom and (especially) my dad wanted.

To them, I wasn’t disabled, and they never treated me as such. To them, I was just a normal kid with a somewhat abnormal condition. That’s why around the house they never gave me special treatment or graded on a curve when it came to the things they expected of me. I was just one more kid in the house and, as such, had chores and responsibilities like everyone else.

But while there might have been a few moments along the way that one might consider “seminal” in my conversion to a full-on, born-again disability advocate, there’s one day in particular that I know I’ll never forget.

But while there might have been a few moments along the way that one might consider “seminal” in my conversion to a full-on, born-again disability advocate, there’s one day in particular that I know I’ll never forget.

I was in my thirties. Young enough to still have a tender heart and a mind like a sponge, but old enough to fully understand that I was now a man – and a man of principle, at that. As such, I was going to have to be willing to take a number of often difficult and unpopular stands over those issues about which I felt most passionate.

We’d just pulled into Penn Station that day from Syracuse. The Downtown Athletic Club in midtown Manhattan was hosting an event that evening to honor the late Heisman Trophy winner, Ernie Davis. And my boss, Assemblyman Mel Zimmer, his boyhood friend, a guy named Carmen Davoli, and I – three of biggest S.U. fans in the world – wanted to be there to help celebrate, arguably, the single greatest sports hero our hometown had ever produced.

The problem was, back then Penn Station had no ramps leading from its trains to the street level – just a handful of stairways that always seemed a constant throb of commuters, tourists and travelers. We searched all around that day for an elevator, but came up empty everywhere we looked. This was after twenty minutes or so of searching.

Finally, frustrated to no end, we asked someone, who told us to go to the far end of the station and take the corridor we found there. At the far end of that corridor, the guy said, we’d find the only elevator in the place. So, by the time the three of us finally opened the door onto Seventh Ave above, we’d spent a full thirty minutes just trying to get out of the damn building.

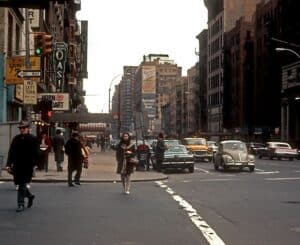

It was now almost five in afternoon, the absolute worst time of day to find a cab in midtown, under the best of circumstances. But we couldn’t hail just any cab. We had to try to find a Checker Cab, whose back seats were large enough to accommodate a wheelchair. After coming up empty, yet again, and wasting yet another thirty minutes of life we’d never get back, we finally decided to walk to the hotel, about fifteen or so blocks uptown toward Central Park.

It was now almost five in afternoon, the absolute worst time of day to find a cab in midtown, under the best of circumstances. But we couldn’t hail just any cab. We had to try to find a Checker Cab, whose back seats were large enough to accommodate a wheelchair. After coming up empty, yet again, and wasting yet another thirty minutes of life we’d never get back, we finally decided to walk to the hotel, about fifteen or so blocks uptown toward Central Park.

Oh, did I happen to mention it was also about 85 degrees that day, with about 90% humidity to boot?

As a result, even before we began working our way uptown, the three of us had already managed to sweat through our tee shirts, our dress shirts and the lightweight sports coats we were all wearing.

Yet, I kid you not, that worst was yet to come.

Because, you see, in addition to the stifling heat and humidity, and the idea we all were toting old-school suitcases – along with the nagging little reality that one of us was in a wheelchair – was fact it was the early 1980’s. As such, there was not a single curb-cut in any of the fifteen or so crosswalks leading up Seventh Ave to our destination. For a guy in a chair, it was just one concrete barrier after another standing between his melting to death in the single most unforgiving city in the world and basking in the air-conditioned comfort of one of that city’s thousands of wildly overpriced hotel rooms.

But what bothered me most that day wasn’t that I was being forced to propel a non-motorized wheelchair up fifteen of the busiest blocks in America. Nor was it that I continued to drip sweat from parts of my body I never even knew existed. It was that my boss at the time, maybe the most remarkable man I would ever meet, and his friend from grammar school (who’d soon become my friend as well), were compelled at the beginning and end of each block, to put down their suitcases, pick up my chair and either lift me up onto the sidewalk or lower me into the street.

By the time the three of us got to our hotel, a full hour after leaving Penn Station, I sat in the lobby with rage in my eyes as my two friends, each drenched in sweat, stood there at the front desk like gentlemen and checked themselves into their respective hotel rooms – their muscles likely aching and the clothes on their backs just as likely to end up in the garbage can as the cleaners.

By the time the three of us got to our hotel, a full hour after leaving Penn Station, I sat in the lobby with rage in my eyes as my two friends, each drenched in sweat, stood there at the front desk like gentlemen and checked themselves into their respective hotel rooms – their muscles likely aching and the clothes on their backs just as likely to end up in the garbage can as the cleaners.

That’s when, like Paul on the road to Damascus, it struck me, and did so with the force of a lightning bolt. Something had to change, I said to myself, right then and there. And, given I was working for a brilliant, hard-working and moral assemblyman from the great state of New York, I told myself was in a perfect situation to strike at the very hornet’s nest that had just forced us to go through what we had. And it was my duty, I told myself, to begin to stir up what, years later, congressman and civil rights legend John Lewis would refer to as “good trouble.”

I realized as I sat there that, from that point on, I was going to dedicate my life to creating a whole boatload of good trouble for the world, as much of it as I could muster in an attempt to help create a more wheelchair-accessible America – or, at the very least, a more wheelchair-accessible New York.

That’s why at the top of this page I refer to myself as an “accidental” warrior. Advocacy was nothing I planned, in other words. It just sort of happened…by accident.

Yet, perhaps surprisingly, when I look back on that day now, I don’t think about the heat and humidity, or my frustration. I don’t think of the sweat running down my back as I wheeled my way to the hotel, or the clothes I tossed in the trash almost as soon as I got there.

Yet, perhaps surprisingly, when I look back on that day now, I don’t think about the heat and humidity, or my frustration. I don’t think of the sweat running down my back as I wheeled my way to the hotel, or the clothes I tossed in the trash almost as soon as I got there.

Nope. The thing I remember most, and the thing I swear I’ll take to my grave, is the sight of two men – two incredibly good, decent and loyal men; one a mentor, the other a guy I’d eventually come to view as a brother from another mother – who gave of themselves so completely, and did so without complaint or any expectation whatsoever.

Yet, even as I write this, I’ve come to realize something else entirely about that day, if not our mutual ordeal. I realize now, as I look back, that as much as I was inspired to try to change my little corner of the world that day, over the course of those fifteen city blocks I somehow also managed to learn something deeper and even more profound about friendship.

Peace be with you, my friends. And God bless. ###

Brian is a hero to me and to many, a man who, among his countless friends who are athletes, stands as tall as any. A true warrior for justice and equality by any other name; I’m proud to call him my friend of nearly 60 years, one whose parting words in every conversation are, “I love you.”

Rex: I'm humbled, my friend. Thank you so much for the kind words. And here's to warriors of all shapes, sizes and stripes, huh?

We love you, Brother!

I love hearing of your triumphs. You may have inspired most of our country which is now so much more disabled accessible. Sidewalks everywhere are now being made with a ramp edge. Doorways are being widened. Congratulations on your many accomplishments. .

Thank you so much, Carolyn. As a society, we still have a ways to go, to be sure. But thanks to so many like-minded crusaders in my generation, we're a lot further down the road than we were, say, eve twenty years ago. Thanks again, and I hope you're doing well!!!

Brian, your victories are further evidence that there is nothing wrong with this country that cannot be fixed by what is right with this country. Your focus on achievement and positivity is an example to be emulated, especially in this time of state-sponsored inertia and cancellation culture. I'm looking forward to the next chapter of your memoir!

Thanks, Michael. I'll keep the stories coming, if you promise to keep reading and keep commenting, OK? I love hearing from you. Stay safe, and my love to you and the whole family!

I never knew the obstacles the disabilities that people like Brian endured until I traveled with him to many sporting events. He opened my eyes forever. One good thing about traveling with Brian is you get great parking places. Love you

Thanks, Tom. And I have to tell you, I loved traveling to all those sporting events (and getting all those great parking spaces) with you. You're a dear friend and an incredible fan. Cheers, my friend! Love you, too.